The Power of Play and Collaboration in AI Writing

How AI Challenges Our Ideas of Originality and Creativity in the Classroom

This post is part of my ongoing field notes on teaching writing in the AI era, exploring how we might rethink creativity and originality in the age of AI. These are thoughts in progress, capturing my reflections as I grapple with these questions alongside colleagues and students.

When was the last time you received a handwritten birthday card? Not a store-bought one with a pre-printed message, but a note crafted from scratch, filled with personal reflections and well-wishes? If you’re like most people, such a gesture feels special, even rare. It carries a weight that a carefully selected store-bought card, no matter how perfect, often doesn’t. Why is that? Both require effort, thought, and care. Yet, the handwritten note is often valued more because it demands originality, while the store-bought card relies on selection, thoughtful evaluation, and creative personalization. This distinction reflects a broader cultural tendency to privilege originality over curation, a tendency that deeply shapes how we view writing and creativity.

This analogy of the birthday card came to me during a summer conversation with colleagues. As we talked about generative AI and its implications for teaching writing, I floated the comparison of a handwritten note versus a store-bought card. The analogy fell flat with the group, but it stuck with me. I kept returning to the analogy, wondering why it resonated so deeply. It felt like an entry point to understanding some of the tensions we face in thinking about writing and creativity today. It’s a useful starting point for examining why we value originality so deeply. These values shape both our resistance to and our acceptance of new ways of writing, including the collaborative, bricolage-like processes that AI enables.

The Myth of Originality and the Playfulness of Bricolage

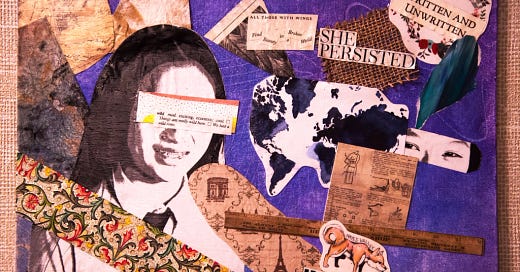

At the heart of this tension is what many have called the myth of originality: the deeply ingrained belief that true creativity and intellectual effort must emerge from an individual’s mind, unassisted and unmediated. This myth, rooted in modernist ideals, romanticizes the “lone genius” and the struggle of creation. Postmodernism, however, offers a contrasting lens, viewing creativity as inherently collaborative, intertextual, and playful. In this framework, the author is a bricoleur—someone who assembles meaning from diverse, pre-existing materials, remixing and recontextualizing them to create something new. Think of a collage versus an oil painting. While the oil painting might represent a singular, cohesive vision painstakingly built from a blank canvas, the collage is an act of assembling, recontextualizing, and blending existing elements to create something fresh and meaningful. Both require skill and intention, yet we often place more cultural value on the oil painting for its perceived originality.

Consider the person who spends a good chunk of time searching for the perfect birthday card. They sift through countless options, evaluating tone, imagery, and message until they find the one that resonates. Then, they add a personal touch—a signature, a short note—to make it their own. This process isn’t passive or lazy; it’s an act of creative discernment. It’s bricolage. And yet, in academic settings, this type of creativity is often dismissed as less valuable than writing “from scratch.”

Why is that? Our cultural and educational frameworks are built on modernist assumptions about thinking and writing. We privilege the struggle of the blank page, the linear process of drafting and revising, and the notion of a singular, authentic voice. These assumptions shape how we teach writing, but they also limit our ability to embrace new tools and methods—like AI—that challenge these norms.

The birthday card analogy helps illuminate how AI might function not as a replacement for human creativity, but as a collaborator in the playful, iterative act of creation.

The Playful Back-and-Forth of AI Collaboration

One of the most exciting possibilities of AI-assisted writing is its potential to make writing more playful and less isolating. Instead of staring at a blank page, students can engage in a dynamic back-and-forth with AI, generating ideas, testing phrases, and iterating on drafts. This process feels less like a struggle and more like an exploratory game—a collaborative conversation with a tool that extends their creative reach.

But this shift can be unsettling. If writing becomes less about individual struggle and more about playful collaboration, what happens to our notions of authorship, originality, and effort? How do we assess work that emerges from bricolage rather than solitary creation?

These questions point to a deeper philosophical divide between modernist and postmodernist approaches to writing. Modernist pedagogy emphasizes individual authorship, linear processes, and mastery of traditional forms of writing, such as academic essays and formal rhetorical structures. Postmodernism, by contrast, embraces collaboration, iteration, and the fluidity of meaning. While I’m not advocating a wholesale shift to a postmodern approach, I believe these ideas offer a useful lens for understanding the present moment.

Room for Skepticism

As always, it’s important to hold space for skepticism. Many teachers—myself included—feel uneasy about the role of AI in writing. What does it mean for students’ critical thinking skills if they rely too heavily on AI-generated content? How do we ensure that writing remains a deeply human act, one that fosters creativity, empathy, and self-expression? These concerns are valid and necessary.

But skepticism doesn’t need to lead to dismissal. In education, skepticism has often led to meaningful pedagogical shifts—consider how early resistance to online learning eventually helped refine its best practices. Rather than dismiss AI outright, we can use our skepticism as a productive tool for inquiry, allowing us to critically examine our pedagogical values and assumptions. In fact, engaging deeply with our skepticism can help us clarify the underlying assumptions that shape our discomfort. If we are uneasy with AI’s role in writing, is it because we fear the loss of effort, originality, or authorship? Or are we responding to a broader shift in how writing itself is being redefined? Rather than rejecting AI outright, we can use our skepticism as a tool for inquiry—one that allows us to critically examine our pedagogical values and assumptions.

Why This Matters

Thinking about the philosophical underpinnings of how we teach a freshman writing class matters because it shapes everything—from the skills we prioritize to how students experience learning. It’s not just abstract theory; these ideas define what we believe writing is for and who we believe our students are as learners and writers.

Aligning with Students' Realities: In a world where collaboration, remixing, and working with technology dominate, holding onto a modernist approach might leave students unprepared for the kinds of writing they’ll actually do in their lives and careers. Teaching as though writing is solitary, linear, or about striving for individual originality can feel disconnected from the collaborative, multimodal, and iterative writing most people now do.

Equity and Access: Modernist approaches often privilege students who already have cultural and educational capital—the ones who are used to excelling in individual, decontextualized tasks. A postmodern approach rooted in bricolage and collaboration acknowledges diverse ways of knowing and working, creating space for students with different strengths and backgrounds to succeed.

Empowering Students: Postmodern approaches can help students see writing as a flexible, adaptive skill. It moves beyond the idea of “correct” writing toward emphasizing how to make choices based on context, purpose, and audience. This empowers students to see themselves as capable communicators in varied, real-world situations.

Reframing the Teacher’s Role: Teachers should care because their role shifts dramatically depending on the philosophical foundation of the course. A modernist approach might frame teachers as gatekeepers of academic conventions, while a postmodern approach positions them as facilitators of exploration, helping students navigate diverse writing contexts and tools.

Preparing for an AI-Integrated World: Philosophical underpinnings are especially crucial now, as AI becomes a larger part of writing. If we hold onto modernist ideals of originality and individual authorship, we may resist tools like AI or stigmatize their use. A postmodern lens encourages us to see AI as one tool among many in the collaborative, bricolage-like process of creating meaning.

Rethinking What “Success” Means: By questioning these underpinnings, we challenge assumptions about what a “successful” writing class produces. Are we teaching students to master academic conventions, or are we helping them become agile, reflective communicators who can adapt their skills across contexts?

This matters not just to instructors but to anyone involved in shaping education—administrators, policymakers, and even students—because how we define and teach writing impacts students’ preparedness for life beyond college.

Shifting Our Thinking as Teachers

How can we, as writing teachers, adapt our thinking to better align with today's emerging writing practices? Here are some starting points to consider:

Reframe Authorship: Teach students that writing is inherently collaborative and intertextual. Encourage them to see AI as a co-creator, not a replacement for their voice. For example, assignments might involve curating and remixing AI-generated content, with reflective components on their creative decisions.

Embrace Playfulness: Introduce low-stakes, experimental exercises that allow students to play with AI tools. Let them explore different tones, styles, and structures without fear of judgment, showing that writing can be a space for exploration rather than perfection.

Focus on Process Over Product: Shift grading criteria to emphasize the writing process. Ask students to document their iterative process, including how they used AI, what they changed, and why.

Decentralize Authority: Move away from the model of the teacher as the sole arbiter of “good writing.” Instead, position yourself as a guide or co-collaborator, helping students navigate the complexities of AI-assisted writing.

Teach Critical Literacy: Equip students to critically analyze AI’s outputs, questioning biases, identifying gaps, and reflecting on the ethical implications of using these tools.

Reflections and Next Steps

This exploration leaves me with more questions than answers, but that’s the nature of field notes. How do we balance the playful possibilities of AI with the need to teach critical thinking and ethical engagement? How do we help students develop their voices while embracing the collaborative nature of writing? And is the modernist/postmodernist terminology even the most effective framework for understanding these shifts, or does it leave essential aspects of this transformation unexamined?

I’m curious to hear your thoughts. How do you see AI reshaping creativity in your classroom? What strategies have you tried, and what challenges have you encountered? Share your experiences in the comments or reply to this email—I’d love to continue this conversation together.

This post was created in collaboration with AI tools, reflecting my commitment to understanding both the potential and limitations of AI in writing instruction.

You comment to focus on process over product makes sense. I like your idea of making students document their leading and state why they changed something or left it as is. It changes the types of journaling that happens but then again maybe not. Finally adding play to the conversation is exactly what we need.

I remember that "originality versus curation" conversation we had and your example of the bday card when we discussed AI in my office this past year, and I was so drawn to your analogy as a way to rethink authorship as pitched to our students, but seeing your writing on this topic has helped to clarify and elucidate even further. Questions that hit me after our conversation and more now, having read your thoughts: how do we shift out of (or disrupt) that arbitrary cultural and historical burden placed on teachers to be expert curators of knowledge and, instead or in conjunction, empower students to see themselves as curators in their own acquisition of knowledge by using AI as a tool? This shift may be at the heart of questioning our current practices around authorship, authenticity, etc. we share with students. I thank you for your careful tracing of the historical power systems impacting what and how we teach, and for showing vulnerability in charting your ongoing research! I'll be following your thoughts and academic musings posted here, for sure, and I look forward to seeing the report from your sabbatical work once you return in fall.